What Accounts for Income and Wealth Inequality Between Countries?

This is my own work and was written between October 2020 - December 2020

What Accounts for Income and Wealth Inequality Between Countries?

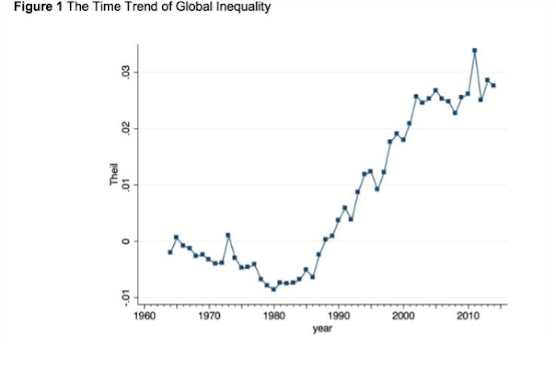

The reasons for income and wealth inequality between countries is complex to answer, it is clear however, that global inequality is rising. Figure 1 shows global inequality has trended upwards since 1986 (Galbraith et al (2020)). This essay focuses on the reasons for inequality between developing and developed countries and will be viewed from the lens of the Developmentalism schools. It will be argued that the reasons for economic inequality between countries goes beyond the views of the conventional Developmentalism school. Income and wealth inequality will be considered within this essay as defined by Davies et al (2018).

Developmentalism is an economic theory that argues increased trade from globalisation is a cause for global inequalities. The Prebisch-Singer hypothesis is a common explanation as to why globalisation causes inequalities, being supported by Arezki et al (2013) using statistical analysis, examining data as far back as 1650. The hypothesis says the value of primary products decline relative to manufactured goods in the long run, leading to worse terms of trade for developing countries. From this we see that nations with long term worsening terms of trade will see income inequality rise as imports become more expensive and primary product exports cheaper. The overall impact on income inequality will depend on elasticity, if the majority of imports are inelastic the rise of income inequality will be most severe. Wealth inequality within developing countries will also widen as the wealthy are less susceptible to both elasticity and general import prices than the poor.

New Developmentalism is a modern outlook, going further than Developmentalism by analysing the role of exchange rates. Galbraith et al (2020) explain that a short-term depreciation in the exchange rate for country ‘A’ between them and country ‘B’ will see a rise of income inequality between both of them. The imports of ‘B’ are now cheaper, meaning income inequality decreases, but imports of ‘A’ now cost more, meaning income inequality between ‘A’ and ‘B’ increases as the price change will affect the poorest more. Contrary to what many economists claim, exchange rates can cause inequality in both the long and short term. “An exchange rate that is overvalued in the long run makes a country’s manufacturing firms uncompetitive, discourages investment, and thereby becomes an obstacle to growth” (Bresser-Pereira (2017)). Therefore, with limited growth, the poorest will not be pulled out of poverty and the inequalities between the countries will remain in the long term. The impact of exchange rate volatility is also apparent on wealth inequality, Galbraith et al (2020) argue “the pay scales of the exporting sectors exceed those who sell only or largely at home” (p. 99), thus, the wealthy who typically export more than the poor will see the majority of the increased revenue from the undervalued currency and will feel a low impact on the increased price of imports.

A flaw of the Developmentalism schools when comparing inequalities between countries is that they ignore the influence of corruption as a major factor. You et al (2004) explain that the wealthy have the ability to engage in corruption and the motivations to extort the poor for their own benefit. They also state that countries with high levels of inequality will likely mean the poor are deprived of vital public services such as education and health care (p.9). This enforces inequality within corrupt countries by keeping the poor uneducated, creating barriers to the paths which help decrease poverty levels. High corruption is therefore a driver in rising inequality, as “Corruption is also likely to reproduce and accentuate existing inequalities.” (p. 34). Corruption may increase wealth inequality between countries as the most corrupt countries will hoard the wealth, which represses income equality as wealth is not redistributed, being concentrated at the top instead.

We will now analyse the correlation between corruption and inequality using statistical evidence from various sources. This will allow us to explore the assertions by comparing the average income and wealth inequality Gini coefficients of the 10 most and least corrupt countries.

Table 1.1

10 Most Corrupt Countries (Transparency International, 2018) | Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) | Most Recent Income Inequality Gini Coefficient Value as % (World Bank, 2020) | 10 Least Corrupt Countries (Transparency International, 2018) | Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) | Most Recent Income Inequality Gini Coefficient Value as % (World Bank, 2020) |

Somalia | 9 | N/A | Denmark | 87 | 28.7 |

South Sudan | 12 | 46.3 | New Zealand | 87 | N/A |

Syria | 13 | N/A | Finland | 86 | 27.4 |

Yemen | 15 | 36.7 | Singapore | 85 | N/A |

Afghanistan | 16 | N/A | Switzerland | 85 | 32.7 |

Venezuela | 16 | 46.9 | Sweden | 85 | 28.8 |

Sudan | 16 | 35.4 | Norway | 84 | 27 |

North Korea | 17 | N/A | Netherlands | 82 | 28.5 |

Haiti | 18 | 41.1 | Luxembourg | 80 | 34.9 |

Democratic Republic of the Congo | 18 | 48.9 | Germany | 80 | 31.9 |

Figure 1.2 can now be constructed using Table 1.1 to show the correlation between the CPI and income inequality Gini coefficient of the known countries. We can see the graph supports the assertion, implying corrupt countries are less income equal than uncorrupted countries.

Table 1.2

10 Most Corrupt Countries (Transparency International, 2018) | Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) | Most Recent Wealth Inequality Gini Coefficient Value as % (Credit Suisse Research Institute, 2019) | 10 Least Corrupt Countries (Transparency International, 2018) | Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) | Most Recent Wealth Inequality Gini Coefficient Value as % (Credit Suisse Research Institute, 2019) |

Somalia | 9 | N/A | Denmark | 87 | 83.8 |

South Sudan | 12 | N/A | New Zealand | 87 | 67.2 |

Syria | 13 | 69.9 | Finland | 86 | 74.2 |

Yemen | 15 | 79.8 | Singapore | 85 | 75.7 |

Afghanistan | 16 | 65.5 | Switzerland | 85 | 70.5 |

Venezuela | 16 | 74.3 | Sweden | 85 | 86.5 |

Sudan | 16 | 68.7 | Norway | 84 | 79.1 |

North Korea | 17 | N/A | Netherlands | 82 | 90.2 |

Haiti | 18 | 80.1 | Luxembourg | 80 | 67 |

Democratic Republic of the Congo | 18 | 75.5 | Germany | 80 | 81.6 |

Figure 1.3 shows that some of the least corrupt countries are less equal than the most corrupt in wealth distribution. This can be easily explained. The majority of the least corrupt countries are European, so there is plenty of ‘old money’ with immense wealth which has compounded over hundreds of years, creating a large wealth divide (Economics Explained (2020)). However, this wealth is somewhat redistributed through progressive inheritance taxes, meaning income inequality is more equalised. Corrupt countries have little ‘old money’ as many are ‘new’ countries, the majority of wealth lies with the political class and is not redistributed to equalise income inequality. We must keep in mind that the data may skew the level of inequality within uncorrupted countries due to ‘old money’ in Europe. The long-term effects of corruption on wealth inequality cannot be realised in new countries, we can likely assume, however, that in the long run it will follow a similar trend as that of income inequality.

Developmentalism places the reasons for income and wealth inequality between developing and developed countries on the rise of globalisation and more recently, exchange rate movements. We found that a rise of inequality within developing countries will likely result in a rise of inequality between developing and developed countries. While Developmentalism has valid explanations, the school fails to account for simplicities such as corruption, where corrupt politicians take advantage of political systems to maintain power by accentuating existing inequalities. To understand the reasons why there are inequalities between developing and developed countries, we can conclude that we must look closely at the economic explanations, but we must also look at and take into account the societal differences.

References

Davies, J.B., & Shorrocks, A.F., 2018. Comparing global inequality of income and wealth. WIDER Working Paper 2018/160. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

Galbraith, J., & Choi, J., 2020. Inequality under globalization: state of knowledge and implications for economics. Issue no. 92. Real-world economics review. pp.84-102.

You, J-S., & Khagram, S., 2004. Inequality and Corruption. KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP04-001.

World Bank, 2020. Gini index (World Bank estimate) [Online]. Available from:

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI/ [Accessed 29/11/2020]

Arezki, R., Hadri, K., Loungani, P., & Rao, Y., 2013. Testing the Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis since 1650: Evidence from Panel Techniques that Allow for Multiple Breaks. Working Paper. IMF: Research Department.

Bresser-Pereira, L.C., 2017. New developmentalism: Macroeconomics for developing countries [Online]. DOC Research Institute. Available from: https://docresearch.org/2017/12/new-developmentalism-macroeconomics-political-economydeveloping-countries/ [Accessed 28/11/2020]

Transparency International, 2018. Corruption Perceptions Index [Online]. Transparency International. Available from: https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2018) [Accessed 16/11/2020].

Credit Suisse Research Institute, 2019. Global Wealth Databook 2019 [Online]. Credit Suisse. Available from: https://www.credit-suisse.com/media/assets/corporate/docs/aboutus/research/publications/global-wealth-databook-2019.pdf [Accessed 1/12/2020]. pp.117 - 120

Economics Explained., 2020. How The Dutch Economy Shows We Can't Reduce Wealth Inequality With Taxes [Online]. Available from:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ot4qdCs54ZE&feature=youtu.be [Accessed 3/12/2020]

Comments

Post a Comment